Graphic Novel Hamlet: Reaching Beyond Stage and Page

DANIELLE TERCEIRO,

Alphacrusis University College

The persistence, abundance, and diversity of Shakespearean adaptations across many media shows Shakespearean narratives to be “successful replicators,” the terminology proposed by Bortolotti and Hutcheon (2007). In the past decade, many graphic novel adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays have been produced. While graphic novels have their own affordances that allow the Shakespearean plays to be assembled for “performance” on the page, at the same time they open up connotations that would not be available in a conventional stage performance. The conventions of the comic book allow storyworlds to be opened, worlds that reach beyond the page and stage, and that exist on different narrative, or diegetic, levels. At the same time, a graphic novel adaptation can highlight the ephemeral nature of performance and the fragile network of human and nonhuman elements that hold together a Shakespeare narrative in performance — whether this performance is on the stage or the page.

This article will examine and compare three graphic novel adaptations of Hamlet: Hamlet (Manga Shakespeare) by Richard Appignanesi and Emma Vieceli (2007) (hereafter referred to as Manga Shakespeare); Hamlet (No Fear Shakespeare Graphic Novels) by Neil Babra (2008) (hereafter referred to as No Fear); and Shakespeare’s Hamlet by Nicki Greenberg (2010). Together these texts show that graphic novels can use comic book conventions to tap into the “agency of adaption” that is inherent in dramatic pretexts. When creating a stage performance, a director must make creative decisions that move outside the explicit instructions of a dramatic text. There is a similar but more complicated agency at work when a dramatic text is brought together as a performance on a page. Shakespearean adaptations bring their own particular joy and complexity, as the pretexts themselves serve as invitations to partake in an intense flux of meaning and mixed ontologies.

Our concerns about the passing down of Shakespearean cultural capital to the next generations may have calcified our idea of what Shakespeare is, that is, canonical Shakespeare is that text written across the page in words. Shakespeare retellings are considered important sites for the enculturation of children (Stephens and McCallum 1998, 255–56), and the idea of fidelity to an authoritative original remains important (Müller 2013, 99). There is a concern that Shakespeare’s heightened verbal language will be forgotten if adaptations for a young readership “translate” his text into contemporary language. In the past these pressures have led to the view that Shakespeare’s dramatic texts must only be read as a self-enclosed verbal text, and not experienced as a performance (Styan 1999, 147). These concerns are often linked to a hierarchical view of art that privileges written sources of narrative. Literature is also often seen as a “one-stage art form,” and this view upholds the “illusion of originality” (Hutcheon 2007). If Shakespearean texts are considered a self-enclosed, one-stage art form, then Shakespeare’s own use of pretexts, collaboration with other authors, and his revision of his own work, highlighted in the “revision theory” within recent Shakespearean scholarship (see Wells 2014, 68–69), are also prone to being overlooked.

Performance criticism has the potential to render our rigid views of what the essence of Shakespeare is into something more liquid and volatile, something that needs a creative team to handle it with care to realise the meaning of the text in performance. Performance criticism considers plays to be scripts that can only be fully realised in a moment of performance. Hutcheon (2007) notes that plays are traditionally seen as “two stage arts,” and a text is moved from page to stage by an entire team of creative individuals. In the context of a graphic novel adaptation of Shakespeare, a “creative team” is often apparent as the text is transformed into a verbal/visual comic medium. In the case of Manga Shakespeare and Hamlet (No Fear Shakespeare Graphic Novels), the verbal and visual texts are composed by different producers. In the latter, Neil Babra is credited as the illustrator. No individual is credited as the adaptor of the verbal text, and an implication is that the No Fear Shakespeare titles incorporate verbal text produced by a creative team, which may or may not include the illustrator. The cover of Shakespeare’s Hamlet notes that the title has been “staged on the page by Nicki Greenberg,” and thus the idea of the author as a director of a performance is implied. The text foregrounds a “creative team” at the end of the text, which lists a “supporting cast and crew.” This list blurs the boundaries between those individuals who are most clearly part of the creative team that helped to produce the text (e.g., “Technical Assistance”), those involved in the publishing industry (“Graphic Novels Visionary & Publisher”), and those who provided personal and emotional support for the author (“Lighting of Life”). The list implies that the author is a creative director, responsible for harnessing all the emotional, technical, and industry resources available to her in the production of the text.

Graphic novel adaptations of written texts inevitably involve a “reverse ekphrasis,” where the comic supplies a surplus of visual stimuli to encourage readers’ connotations. A graphic novel adaptation of Shakespeare can make the visual aspects of performance more explicit, even as it cannot replicate them exactly. It has the potential to retrieve some of the rich aesthetic exchange that has occurred in the past between art and performance, for example, during the process of “montage and transposition” that occurred with respect to highly coded “cultural objects” in fifteenth century European art and performance (De Marinis, 1993, 128). According to Bartosch and Stuhlmann (2013, 59), the comic is a central medium in an accelerating “convergence culture,” and the semiotic resources it has available to it place it between traditional literature and film. This understanding of comic affordances is consistent with Stam’s proposed “adaptation as translation” approach (Stam 2000, 62). Adaptations across different modes and media are accompanied by the “losses and gains” typical of any translation.

However, it also needs to be considered how, or to what extent, “adaptation as translation” is the appropriate lens with which to consider the adaptations of a dramatic text. Shakespeare’s plays are dramatic texts, created to be performed on the stage. The texts imply an audience that experiences visual and verbal stimuli during a performance. It is only the “idea” of performance that can be created in the mind of a reader of the written text. According to Styan (1999, 3), a play is completed by a spectator’s act of perception. The code of signals in the text waiting to be deciphered by the actors must be matched by that contrived by the audience, for the play comes alive only by the creative act of synthesizing what is seen and heard and accommodating this to what the audience already knows and feels. Styan considers Shakespeare to be a master synthesizer: “In performance Shakespeare anticipates every problem of illusion, and his plays are our best example of the self-conscious, convention-bound art of drama at its liveliest” (1999, 90). The ultimate question about a performance is “Does it work?” A play must communicate or it is nothing (Styan 1999, 6). Literary insights into Shakespeare’s imagery, for example, must still be tested on the stage to see whether the verbal concept supports what the eye sees.

Hamlet shows Shakespeare’s expert handling of stage conventions to create meaning. Rozik (2008) refers to Hamlet’s soliloquies as a particularly strong use of stage convention — signalling to the audience that his words here are much more consequential than, for example, his words with Polonius or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (70). In Hamlet, a self-conscious metatheatrical aspect is also evident in the staging of the “mousetrap” play before the King and Queen (3.2), and also thematically present in Hamlet’s “performed” madness. Can graphic novel adaptations capture these self-conscious metatheatrical aspects of Shakespeare’s plays, even in the absence of a physical performance of the dramatic text? If so, in what ways can this self-consciousness be different from a staged performance?

Puchner (2011, 294–96) considers that there are three ways to understand the relationship between a dramatic text and performance:

| ◆ the dramatic text as a set of instructions; |

| ◆ the dramatic text as an incomplete artwork, a work with gaps that actors, designers, and directors must fill; or |

| ◆ the performance of any dramatic text as necessarily involving transformation and adaptation. There is nothing in the text, complete though it is, to give definite instructions. The agency of adaption resides with the adaptor, even though this adaption occurs within a set of constraints. Any text, including ones that do not look like plays at all, can become “dramatic”: a dramatic text is defined simply as a text that has been adapted to the stage. |

This article considers that the third formulation of the relationship between dramatic text and performance can be extrapolated to a situation in which a dramatic text is adapted into a non-performance medium (e.g., a graphic novel). The “agency of adaption” that applies to the director of a performance can also be applied to the producer/s of a graphic novel adaptation. This is because assembling a play for performance on a page can involve the same agency as assembling a play for performance on a stage.

Hamlet and the Ephemeral “Network of Connectedness”

Actor-network theory (Latour 2005) is a helpful lens to use to focus in on adaptations of Shakespeare, and the agency that producers of adapted texts have as they assemble a “performance.” Actor- network theory emphasises the fragile, changing, and ephemeral nature of social phenomena. It is not a critical lens in that it does not seek to deconstruct a given. Rather it looks at how groups or “ensembles” are formed, what human and nonhuman resources are mobilised to “make the group boundary hold out” at the point at which the social is performed (Latour 2005, 33). Observers of the social cannot decide in advance, and in place of the “actors” (human and nonhuman) what sorts of social blocks the social world will be made of (41). Shakespeare’s plays are an apt site of performance in which to observe how the social can be assembled and represented in a text, as he “can be seen as a thinker of multiplicity and movement who mixes up different periods and ontologies” (Gil Harris 2010, 61). This article will explore the network of connectedness, encompassing verbal and visual communication, that is constructed and relied upon in the production of the selected texts. In the case of media transformation, it is important to extend this network to include recipients, production contexts, and sociocultural and aesthetic factors (Schober 2013, 103).

In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the ephemeral nature of the “network of connectedness” that is assembled in the text, is foregrounded by the deaths of the main performers at the closing of the narrative, which occurs after the curtain falls. The text also highlights the transient nature of the network of varied production contexts and sociocultural and aesthetic factors “assembled” for the purpose of this text. The sequins and lace that are featured between scenes highlight the material means of producing a performance; the romantic interactions of those working behind the scenes highlight a unique production context; and the ticket stubs and posters evoke a “gay Paree” aesthetic. Shakespeare’s Hamlet demonstrates the greatest commitment to the replication of Shakespeare’s original language, however, the note on the cover that this text has been “staged on the page,” along with the other aspects of the text outlined above, highlight the ephemeral nature of dramatic performance, and position the text as a representation of a unique constellation of events.

In Manga Shakespeare the text is framed by an introduction which sets the story within a future environmental dystopia, a “cyberworld in constant dread of war.” This explicit framing of the text as occurring within a type of dystopia commonly portrayed in young adult literature and in film, in combination with its explicit description as a “manga” text, foregrounds the many aspects of popular culture that have been assembled for the purpose of this Hamlet adaptation. By contrast, No Fear is a more “straightforward” comic version, which sets the story in a setting that is recognisably medieval. The back cover, which shows Hamlet in a sword fight and refers to his struggle “to deliver justice on his own terms,” implies an audience that is familiar with superhero comics. The young Fortinbras is depicted differently than the other characters, with hair and angular facial features reminiscent of a villain in a superhero comic. Fortinbras’ entry at the end of the text (203), and his decisive military role in the concluding events of the narrative, suggests that this kind of “comic” reference can help to provide a satisfying closure for the implied audience of a graphic novel adaptation.

It may be that Hamlet is a pretext that particularly invites unstable and ephemeral constructions of subjectivity. Styan (1999, 145) considers that in the case of Hamlet there is a long tradition of literary criticism that treats the play as a “blob of ink, folding it in two and finding in the play an image of oneself.” Styan (1999, 145) refers to William Hazlitt (1817) as the first in “this procession,” when he claimed that “[i]t is we who are Hamlet . . . , he to whom the universe seems infinite, and himself nothing.” Eliot (1919) considered that Hamlet the character has an “especial temptation” for the weak critical mind, which often finds in Hamlet a vicarious existence for their own artistic realization. Shakespeare’s Hamlet foregrounds the process of artistic realization that occurs behind the scenes in a production of Hamlet by introducing the Hamlet player as a faceless, ink-black character, who attaches his “face” to his black body before curtain call.

Müller (2013, 103) refers to the “masking effect” of comic images, in which deliberately stylized lines and bland faces invite reader identification, because the blandness of the figure’s faces leaves more room for the readers to project themselves onto those faces. This masking effect is particularly evident in Manga Shakespeare and its use of manga conventions to represent faces. Many of the facial close-ups include incompletely rendered facial features which “free float” across a blank background (15, 25, 29, 167, for example). These close-ups function similarly to a film close-up, which foregrounds the cognitive processes of the person, but also foreground (in a way in which film cannot), that the particularity of a character’s physical appearance is not necessary (and perhaps is counterproductive) when seeking to inspire empathy in an audience. The “masking effect” in the case of Manga Shakespeare could also be referred to as an “avatar effect”: a device which invites the reader to “play the game” as one of the characters.

Storyworlds Beyond Stage and Page

A cognitive approach to the concept of “storyworld” considers how a world is constructed within a narrative and “simulated” within the mind of a reader, and what kind of cues trigger this process of simulation (Ryan 2014, 31). “Storyworld” offers a basis for distinguishing between intradiegetic and extradiegetic elements of a narrative, and it is a helpful concept in the context of the comic medium, which tends to be full of verbal and visual elements that do not belong to a storyworld (Ryan 2014, 34–35). Images may not correspond to objects that exist in the real world, or there may be an extradiegetic narrator. Multimodal texts can problematize the relationship between text and image by introducing images that do not relate in obvious ways to the content of the text or that originate in a different world (Ryan 2014, 35). These images may be “ad hoc pointers” that point the reader to a “non-literal,” conative reading of word and image (Yus 2009, 155).

The creation of storyworlds is relevant to the performance of a canonized dramatic text, such as a Shakespearean text. It can be understood as analogous to the process of “re-contextualization” that occurs in the contemporary performance of a Greek play. Sidiropolou (2014, 37–38) notes that:

| An integral part of re-contextualization is the construction of a self-contained universe on stage that bears its own rules and celebrates its own semiology. Frequently the visual layering of the production bears little relation to the language of the text and therefore dialogue, action and setting stand in opposition to each other. This tension can induce patterns of defamiliarization and forces us to look beyond the expected for a deeper connection between text and sub-text. |

This links us back to the discussion of actor-network theory. As Latour notes, it is important to “notice the metaphysical innovations proposed” by the actors within a network, and one cannot take for granted the presence of the social: it has to be demonstrated every time (2005, 51–53). A metaphor that Latour considers particularly helpful in understanding the social is that of the stage, where action is dislocated rather than a “clean-edged affair”:

| As soon as the play starts . . . nothing is certain: Is this for real? Is it fake? Does the audience’s reaction count? What about the lighting? What is the backstage crew doing? Is the playwright’s message faithfully transported or hopelessly bungled? Is the character carried over? And if so, by what? What are the parties doing? Where is the prompter? (46) |

These anxieties are present for every stage performance, they are present as we consider every fragile construction of the social, and they are more or less foregrounded in texts, such as graphic novels, that represent a storyworld or storyworlds that are derived from a dramatic text and cannot help but reference previous stage performances.

The multimodal graphic novel is a medium that reminds its audience that the same phenomenon can be conceptualized and represented in different ways, or “world versions” (Hallet 2014, 162). It can assemble what Sidiropolou refers to as a “self-contained universe,” or what Latour might refer to as a network. However, the multimodal novel also makes it possible to both represent and critique the space and motion of experienced reality on a “metasemiotic level” (Hallet 2014, 162), in a manner that reminds us of the inevitable “dislocation” Latour refers to in the construction of the social. For example, Manga Shakespeare complicates the storyworld in his text, and calls into question the idea that there can be a self-contained universe with clean edges, by showing different “layers of reality” in the depiction of Ophelia. Ophelia is introduced to the text by showing an image of her within a virtual world of nature and music (26, fig. 1), a world which can only exist virtually in the environmental dystopia of this adaptation. Other depictions of Ophelia show her clothing patterned with what appears to be a digital overlay and show her background as a digital wallpaper with repeated pattern (for example the flowers and rose petals on pages 30–31, fig. 2). The effect is to show Ophelia as dependent on the virtual world in the context of a “real” world that provides her with little emotional support, and no interaction with nature. The character which has the most affinity with nature is depicted as (necessarily) the most reliant on technology to provide a substitute sensory experience. Ophelia’s “breakdown” is shown by the breakdown of her character into a sketchy modality, and the flowers which trail her, and appear to belong to an extradiegetic digital world (133–34). She also has a sketchy modality in the depiction of her drowning, and this illustration also depicts a castle covered with digital wallpaper (156). The collapse of “real world” and “digital” storyworlds foregrounds Ophelia’s own cognitive collapse.

Figure 1. Manga Shakespeare, 30–31

Figure 2. Manga Shakespeare, 26–17

In No Fear, the depiction of the player’s rendition of Hecuba’s grief opens many extra-diegetic layers. On page 71, the last panel illustrates the player’s tearful face as he imagines a “burning eye of heaven” watching a grieving Hecuba. The image of Hecuba and the eye lie above the player’s cloud-like speech bubble, highlighting both the imaginative world of the player, and the supernatural world. These worlds are foregrounded again on page 74 (fig. 3), where the second to last panel shows Hamlet remembering the emotion of the player. The last panel on page 74 shows a large hand emerging from fire, pushing Hamlet up a steep hill. The verbal text references Hamlet’s “motive and cue for passion,” and the illustrations show that this passion is prompted by a person who is “larger than life” for Hamlet, and that the passions of Hamlet’s father (which Hamlet considers should be the motive and cue for his own passion) are stoked by the supernatural fires of Hades.

Figure 3. No Fear, 74

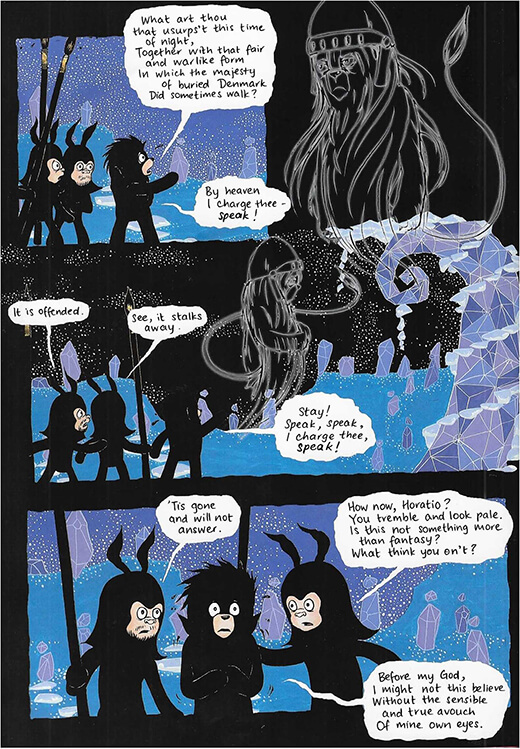

Shakespeare’s Hamlet merges the storyworld surrounding a “real-world performance” with a messy blurring with digital fantasy worlds. The “performance storyworld” is established at the outset: the cover notes that the title has been “staged on the page by Nicki Greenberg” and positions the reader as the “audience” to a staged version of Hamlet through the first three pages of the text, which are black and advise the reader to be quiet (“shhh . . . ”). The beginning of act 1, scene 1 (2–3) shows a space bounded by curtains, suggesting the existence of a stage. However, the background to the guard character is a digital-looking background, with a flatness of perspective that suggests a computer game, or that it is a video or photographic image that has been altered in post-production. The background includes crystal-like structures that do not relate to a material historical setting (whether medieval or early modern). Elements of this background are delineated against a black “sky” as the ghost of Hamlet’s father “stalks away” across the landscape (8, fig. 4). This “breaking down” of a flat background occurs throughout the text, and on occasion the background morphs to foreground an emotion or image in the verbal text. For example, Ophelia’s “swirl” of madness is shown by the distortion of a cog background (307). The overall effect of the backgrounds in Shakespeare’s Hamlet is to suggest that what is “staged on the page” is not limited to a mimetic representation of an event (the historic performance of a play). What is “staged on the page” in this text is staged against digital, malleable canvases that are visually figurative representations of perceived consciousness.

Figure 4. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, 8

The assertiveness of a storyworld and the cleanness of its edges can be tempered via other visual means. Changes in visual modality can induce a “semiotic break” that invites a reader to “change the gears” of their reading and consider connotative implications. Any break in the code, reminds readers they are looking at a drawing and so combats or weakens the fictional illusion of a storyworld (Groensteen 2013, chapter 5). In Manga Shakespeare, for example, there are switches to a more basic, childlike depiction of the characters in the story (28, 56, 93, 95). These switches occur when there is suspicion that a character is “playing” at something, for example, Hamlet’s sarcastic and cutting humour as he lies in Ophelia’s lap (93), and the humorous repartee of Hamlet and the gravediggers (161).

Shakespeare’s Hamlet uses a double page between each scene, depicting a “behind the scenes” scenario while showing the interactions between actors. These double pages disrupt the rhythm of the text by making the timing of the character’s interactions more ambiguous, and it problematizes the diegetic temporality of the narrative. They do not contain comic panels, and make use of collage to foreground the stage, the set, curtains, and other materials such as props and stagecraft. For example, pages 242–43 show the characters standing on a floor that, even though it appears to be a collage derived from cardboard, evokes a stage-floor “woodenness,” and a number of props stand against the wall, including the large cog which trapped the king within the “massy wheel” (232). It is not clear whether these interactions occur backstage between performances of each scene, or whether they compress and link the interactions of characters during the whole course of production (including all rehearsals and all performances). The effect is to highlight the emotional effect that a play might have on its characters, for example, the sexual tension sparked between the characters playing Hamlet and Ophelia. They also encourage reader agency in constructing a coherent “performance backstory” that is not laid out explicitly in the text.

The play offers several examples of what has been called “simultaneous staging,” whereby an audience is asked to witness, balance, and weigh several things happening on the stage at one time (Styan 1999, 155). The way in which this is coordinated for an audience highlights the precarious nature of the assembled, performative network, and its need for a “vehicle” for it to travel: “Even to detect Polonius behind the arras that became his shroud, the Prince of Denmark needed to hear the squeak of a rat” (Latour 2005, 53). An example of simultaneous staging occurs with Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy in act 3, scene 1, which does not include directions for exit. During Hamlet’s soliloquy Ophelia is often presented on stage as kneeling in prayer, and Polonius and the king as listening and plotting. In performance, the audience would be looking for the eavesdroppers even if they are not exactly “on stage” (Styan 1999, 155). No Fear “opens” this soliloquy by showing two panels, one with the king, and one with Ophelia, next to a curtain (81, fig. 5). This signals to the reader that this event is focalised by more than one consciousness. The directionality of the narrative is disrupted by the long vertical panel that shows Hamlet asking the question, which sits to the left of three panels that continue the soliloquy. This, in combination with the “ad hoc pointers” that point to connotative interpretations — Hamlet’s shadow skeleton, the tentacles of a tongue — dilate the moment, slowing the tempo of reading. A similar panel layout on the following page (82), and dense connotative imagery continues this dilated moment.

Figure 5. No Fear, 81

Manga Shakespeare dilates the moment of Hamlet’s soliloquy by interrupting the rhythm through a shift in the panel layout of the text: the text moves to a double page with two images that each cover a page. The rhythm is slowed, and the diegetic temporality is also “cracked” into two: Hamlet is pictured on page 78 (fig. 6) as holding a prone version of himself. It is a juxtaposition of the frustrations of an active, furiously thinking Hamlet, against the passive “cowardly” version of Hamlet who vetoes any action. This splitting of Hamlet into active and passive is also highlighted by the two panel insets on this opening, which frame Hamlet’s lips and then his eyes and nose. The large image of Hamlet on page 79, by contrast, has no facial features at all. Hamlet’s alienation, his fragmentation of his sense of self, is foregrounded in this use of comic panels. The sense of Hamlet’s own alienation from himself is also shown on page 90, when two panels split Hamlet’s face horizontally, suggesting a disconnect between what he is saying and what he is thinking.

Figure 6. Manga Shakespeare, 78–79

Another example of “simultaneous staging” that occurs within Hamlet is the staging of the “mousetrap” play in front of Hamlet, Horatio, Ophelia, the King and Queen in act 3, scene 1. Audiences of the stage play would be cued to take alternate note of the mousetrap play itself, the reaction of the King and Queen to this play, and the reactions of Hamlet and others as they perceive the reactions to the play. Manga Shakespeare foregrounds this as a moment which “hangs” on the simultaneous experience of a moment of the mousetrap play, by showing a horizontal grid of characters across the bottom of page 100 (fig. 7). Ophelia is the only character depicted with two eyes, suggesting that the characters have different, incomplete, and less than “clear-eyed” evaluations of the moment. This suggestion is reinforced by a bubble containing an ellipsis, which floats above the grid and breaks Hamlet’s frame.

Figure 7. Manga Shakespeare, 100

The apparent “real life” death of the main actors at the conclusion of Shakespeare’s Hamlet (fig. 8) is consistent with a view of theatre performance as “a kind of ecstasy, an act so inspired and irrational that — at its extremes — it can seem vulgar, lunatic and dangerous” (John Lahr, quoted by Styan 1999, 7). The actors’ deaths are an extreme result of their emotional expenditures during performance (as represented by the pools of ink), and there is irony in the fact that the only recognisable aspect of the actors, grieved over by the other characters, are the “masks” worn by each ink blot. The wraiths of the actors on page 421 are similar to the wraith of Hamlet’s father on page 8. Like the wraith of Hamlet’s father, these wraiths are set against black; however, this black blends with a closed stage curtain. There is thus another blurring of story levels here — between the “after-life” of death, and the “after-life” of a stage performance. This is a kind of reverse of the “ghosting” process that can exist in a stage performance, where attention is drawn to an actor at the expense of a stage figure (Marvin Carlson, as referred to by Rozik (2008, 181). Carlson’s ghosting assumes that the stage character suffers some kind of death. In this text, by contrast, it is the stage actors themselves who suffer a kind of “ghosting” because of the demands of their stage character.

Figure 8. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, 418

These deaths raise performance questions for the reader which step outside of the original storyworld of Hamlet. Are the forceful effects of emotion represented as impacting the characters within the dramatic text, or, does an effective performance require these forces to impact the actors themselves? Hamlet wonders at the ability of the players to seemingly experience emotion on behalf of a fictional character (“And all for nothing! For Hecuba!” [2.2]). Hamlet also demonstrates an ambivalence towards “over-emotional” acting that oversteps the “modesty of nature” when he advises that “in the very torrent, tempest, and, as may say whirlwind of your passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness” (3.2).

Shakespeare’s Hamlet steps away from the some of the imagery in the pretext (for example, passion as a “whirlwind”), and instead focuses on the embodied experience by representing emotions as an energetic force that causes the “ink” of the characters to melt, fragment, or explode. The inky materiality of the characters is foregrounded, as well as the fact that a dramatic performance must involve real people with real emotions, which may be forces that “act” upon them during the performance. After Ophelia melts into a pool of ink at the end of act 3, scene 2, the actor that plays Hamlet is shown as clapping the performance of a smiling, reconfigured (if still dripping) Ophelia and on the next page is shown as making love to her backstage. After Ophelia descends into madness, her character is shown walking towards the wings of the stage with a sad face and dejected pose. The implication of these “backstage interludes” is that the emotional impact of performance can carry over to the actor’s “real life” social interactions. Greenberg’s actors do not apparently have the “temperance” and “modesty” that Hamlet recommends, and they suffer as a result. This emotional excess adds an ironic layer to this text: not only does this storyworld lack temperance, but by displaying this backstage life it disrupts the balance that a stage performance might be able to achieve between the human experience depicted within Hamlet and the value systems of the audience. Rozik notes that “a fictional world is actually structured to either suit aesthetic experiences or not” (2008, 70). This text, because of its propensity to upend a secure meaning-making process, shows that it is not structured with a focus on unity, wholeness, and proportion — it is not assembled with the aesthetic comfort of its audience in mind.

The three graphic novels are, by virtue of their multimodality, an example of an art form that is not a self-enclosed form of verbal text. Each of the texts reaches out to other forms of culture, such as manga and/or super-hero comics, and incorporates cultural references into a Shakespearean adaptation with ephemeral networks of connectedness. The visual aspects of the storyworld in these graphic novels do not, like film, need to depict a fully furnished storyworld with clean edges, and it is often that which is obviously absent from an image within a panel, such as facial detail, which draws the attention of the reader to an aspect of the text. Hamlet is a text that “plays” with many aspects of performance, and, of the three texts, it is Shakespeare’s Hamlet that “latches” on to the metatheatrical aspects of Hamlet and problematizes the relationship between performance and “real life,” as well as the afterlife. Like Hamlet’s father, actors “stalk” the pages of Greenberg’s adaptation, and the taxing and possibly deadly aspect of the acting endeavour has been highlighted. One wonders whether, and how, the ghosts of these actors will be released from their theatrical Hades.

Appignanesi, Richard. See Shakespeare, William.

Bartosch, Sebastian, and Andreas Stuhlmann. 2013. “Reconsidering Adaptation as Translation: The Comic in Between.” Studies in Comics 4 (1): 59–73.

Bortolotti, Gary R., and Linda Hutcheon. 2007. “On the Origin of Adaptations: Rethinking Fidelity Discourse and ‘Success’ — Biologically.” New Literary History 38 (3): 443–58.

Babra, Neil, and William Shakespeare. 2008. Hamlet (No Fear Shakespeare Graphic Novels). New York: Spark Publishing.

De Marinis, Marco. 1993. The Semiotics of Performance. Translated by Aine O’Healy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Eliot, T. S. Hamlet and His Problems, 1919. http://www.bartleby.com/200/sw9.html.

Gil Harris, Jonathan. 2010. Shakespeare and Literary Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greenberg, Nicki. 2010. Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Crows Nest, AU: Allen & Unwin.

Groensteen, Thierry. 2013. Comics and Narration. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Hallet, Charles. 2014. “The Rise of the Multimodal Novel: Generic Change and its Narratological Implications.” In Storyworlds across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology, edited by Marie-Laure Ryan and Jan-Noel Thon, 151–66. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hutcheon, Linda. 2007. “In Defence of Literary Adaptation as Cultural Production.” M/C Journal 10(2). http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0705/01-hutcheon.php.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, Anja. 2013. “Shakespeare Comic Books: Visualising the Bard for a Young Audience.” In Adapting Canonical Texts in Children’s Literature, edited by Anja Müller, 95–111. New York: Bloomsbury.

Puchner, Martin. 2011. “Drama and Performance: Toward a Theory of Adaptation.” Common Knowledge 17 (2): 292–305.

Rozik, Eli. 2008. Generating Theatre Meaning: A Theory and Methodology of Performance Analysis. Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2014. “Story/ Worlds/ Media: Tuning the Instruments of a Media-Conscious Narratology. In Storyworlds across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology, edited by Marie-Laure Ryan and Jan-Noel Thon, 25–49. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Schober, Regina. 2013. “Adaptations as Connection–Transmediality Reconsidered.” In Adaptation Studies: New Challenges, New Directions, edited by Jørgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik and Eirik Frisvold Hanssen, 89–110. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Shakespeare,William. 2007. Hamlet. Adapted by Richard Appignanesi. Illustrated by Emma Vieceli. Manga Shakespeare Series. London: SelfMadeHero.

Sidiropoulou, Avra. 2014. “Adaptation, Re-Contextualisation, and Metaphor: Auteur Directors and the Staging of Greek Tragedy.” Adaptation 8 (1): 31–49.

Stam, Robert. 2000. “Beyond Infidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation.” In Adaptation, edited by James Naremore, 54–76. London: Althlone Press.

Stephens, John, and Robyn McCallum. 1998. Retelling Stories, Framing Culture. New York: Routledge.

Styan, J. L. 1999. Perspectives on Shakespeare in Performance. New York: Peter Lang.

Wells, Stanley, and Anne Sophie Haahr Refskou. 2014. “Shakespeare, Globalization, and the Digital Revolution.” New Theatre Quarterly 30 (1): 65–71.

Yus, Francisco. 2009. “Visual Metaphor Versus Verbal Metaphor: A Unified Account.” In Multimodal Metaphor, edited by Charles J. Forceville and Eduardo Urios-Aparisi, 147–72. Applications of Cognitive Linguistics 11. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.